On Tuesday July 14th at 12:49 BST, the New Horizons spacecraft will fly past Pluto, the ninth planet in our solar system. But why is it there and what is it looking for?

Is Pluto a Planet?

First of all we should probably discuss this as there’s been a lot of confusion about it in recent years. Pluto was discovered in 1930 by an American astronomer called Clyde Tombaugh; it was named by an 11 year old English girl called Venetia Burney, who was very interested in classical mythology (Pluto was the ancient Greek god of the underworld). In 2003 the discovery of another, larger planet beyond Pluto prompted astronomers to reconsider whether Pluto was actually big enough to be a planet at all.

Pluto is only 2,300 kilometres across, making it roughly half the width of the United States and slightly smaller than Earth’s Moon. It is located in the Kuiper (pronounced KY-per) Belt, and has an oval orbit, which means that its distance from the Sun varies. On average it’s 5.8 billion kilometres away from the Sun, which is 40 times further than the Earth. Because of its size and distance, astronomers decided that Pluto wasn’t actually a planet at all but a dwarf planet.

What Do we Know about Pluto?

It’s very cold! Because Pluto is so far from the Sun, its temperature is between -238 and -218 degrees Celsius. It takes 248 years for Pluto to orbit the Sun once, and one day on Pluto is almost 6 and a half Earth days. Its gravity is only one fifteenth of Earth’s, so a person who weighed 100kg on Earth would only weigh about 7kg on Pluto. Interestingly, because of Pluto’s oval orbit, for about 20 years in every 248 it’s closer to the Sun than Neptune is!

Pluto has 5 moons of varying sizes. The largest is Charon (pronounced KEHR-on or sometimes SHEHR-on), which has a diameter of 1172 kilometres. This makes it about half the size of Pluto, and some astronomers believe that Pluto and Charon are actually a binary system, which occurs when two planets orbit each other. The other moons are a lot smaller and are called Nix, Hydra, Kerberos and Styx; there may be others that haven’t been discovered yet.

What is New Horizons?

On January 19th, 2006 NASA launched a probe called New Horizons. About the size of a baby grand piano and similar in shape, it weighed about 480kg when it was fully fuelled for launch. It carries 7 scientific instruments that can examine Pluto’s atmosphere, particles and surface composition as well as measuring the solar wind and taking high resolution images of Pluto’s surface. After 9 and a half years travelling though space, New Horizons will pass Pluto at a distance of less than 13,000 kilometres and will send all the data it records back to Earth as it travels deeper into the Kuiper Belt.

Why go to Pluto?

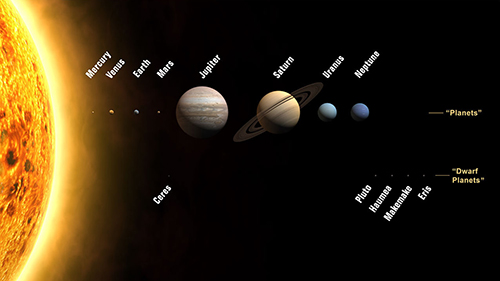

There are three kinds of planet in our solar system: worlds of rock and metal (Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars), gas and ice giants (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune), and ice dwarfs (the dwarf planets in the Kuiper Belt). We know a lot about the first two classes of planet, and the Kuiper Belt is the only part of our solar system that we haven’t sent probes to. Scientists hope that New Horizons will help us to understand what conditions are like so far away from our Sun.

In addition, the ice dwarfs were formed about 4 billion years ago, long before the rest of the planets in our system, and have a lot to teach us about how planets are made. Pluto’s atmosphere is escaping into space, just as Earth’s original hydrogen/helium atmosphere is believed to have, and examining it may tell us about how our own atmosphere came to be. The Kuiper Belt is also the major source of cometary impactors or meteors that hit Earth, possibly including the impact responsible for the extinction of the dinosaurs. To investigate these impactors New Horizons will catalogue the craters on Pluto and its moons.

The last reason for sending a probe to Pluto is the simplest – to explore and discover new knowledge!

Check out this website for more information, and to keep up with the latest developments.

All images © 2015 The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory LLC. All rights reserved.