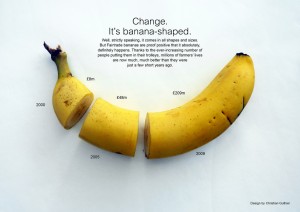

You might have seen the logo – stuck to bananas, in the corner of chocolate bars or perhaps on the label of jars of coffee or boxes of tea stacked on the supermarket shelves. But have you ever wondered exactly what the table ‘Fairtrade banana’ means and who it helps? Clara Wiggins explains all.

Until recently I lived in St Lucia, a small island in the Eastern Caribbean. A beautiful piece of paradise, St Lucia is one of the many islands in that part of the world that has relied for years on a combination of income from tourism and the sales of its fruit and vegetables – specifically bananas – to gives its people a reasonable standing of living. Life on these small islands is tough, they are very vulnerable to things like hurricanes and outside events that stop tourists coming on holiday. But as long as people bought their produce, the people of St Lucia were able to get by and children were able to go to school and get a good education.

Unfortunately, things changed. A few years ago, a change in trade laws meant that the UK stopped buying so many of their bananas from St Lucia and other islands in that part of the Caribbean – known as the Windward Islands – and started buying more of them from Latin America and West Africa.

Supermarkets in this country also became increasingly competitive and wanted to offer their customers cheaper produce to buy. As bananas have always traditionally been one of the most popular items for supermarket shoppers, these were offered at lower and lower prices – meaning the farmers who were growing them were getting paid less and all the people who relied on their income were finding it harder and harder to survive.

This is where Fairtrade stepped in. As an organisation, the Fairtrade Foundation ensures that farmers and other producers are offered a fair and stable price for their goods – and at the same time help improve the working and living conditions of the workers and their families.

After the changes to the trading laws meant fewer bananas were bought from St Lucia and the other islands, the number of banana farmers dropped from 27,000 to around 4,000 – which led to high unemployment, youth unrest and an increase in poverty. But the first consignment of Fairtrade bananas was shipped to the UK in 2000 and since then volumes have grown until today more than 90% of the farmers in the Windwards belong to a Fairtrade group. The knowledge that they will get a good price for their fruit has changed the lives of the farmers. Now they can afford things that we take for granted, like health care and decent education for their children. It also means they can use the money to invest in expanding into other areas and hopefully build back up the number of people employed in this work.

Of course Fairtrade isn’t just about bananas from the Caribbean – you can now buy a huge range of goods including chocolate, flowers, rice, sugar, even beauty products all stamped with the Fairtrade logo from countries across the globe. And every time you do so, you know you are helping someone like the banana farmers to build a better future for themselves and their families.

But as well as buying Fairtrade goods, another way to get involved is to turn your own school into a Fairtrade school.

A Fairtrade school is one that uses Fairtrade products as far as possible, commits itself to learning about how global trade works and why Fairtrade is important and takes action for Fairtrade in the school and wider community. Already, there are nearly 500 schools with Fairtrade status, with many more going through the process to gain certification.

As well as all the obvious reasons for doing it – ie helping the world become a fairer place and helping to reduce poverty – being part of a campaign to get your own school to become a Fairtrade School has many benefits closer to home. It could help you to develop your own skills, have a positive influence on your local school community and – above all – it can be great fun.

For more information on Fairtrade schools you can check out the Fairtrade Schools website

Check out the Fairtrade website to find out what other goods are available.

Traidcraft is anorganisation that campaigns for Fairtrade and can help your school to become a Fairtrade school.

If you enjoyed this article, don’t forget to click on the little <3 next to the title.

Clara is a trained journalist who worked in newspapers for several years before leaving the profession to travel round the world. On her return to the UK, she joined the Foreign Office where she worked in London and then at the British High Commission in Kingston, Jamaica. In 2005 she had her first daughter, followed by her second in 2007. She left the FCO to become a stay at home mother and to accompany her husband on postings to Pakistan and St Lucia. Now living back in the UK, she is currently training to be an antenatal teacher, writing freelance and planning a book about trailing spouses.

Featured Image

Banana Image

Windward Islands Image

Read More...