When you write a book that is set in a particular period of history, it is important to get the details correct. This means that writers of historical fiction have to do a lot of research.

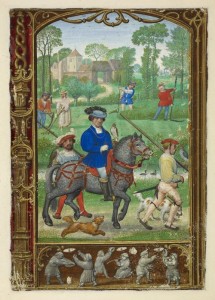

The first scene of Katharine Edgar’s novel, Five Wounds takes place on a hillside in sixteenth century England, where her heroine, Nan, is hoping to see her young merlin falcon make its first kill. Katharine had find out all about falconry and the Tudors – the keeping and training of falcons, and other birds of prey.

When I showed the first scene of Five Wounds to some writing friends, some of them asked a question I wasn’t expecting. ‘How rich is Nan’s family? They live in a big house so why does she need to hunt for food?’

Good question!

And the answer is, that one of the ways the people of Tudor England were very, very different from us, is their interest in hunting with hawks, known as falconry.

Today, falconry is a very unusual hobby. (My plumber does it! When not fixing our taps he flies Harris hawks. But he’s the only falconer I know.)

In Tudor England it was huge and cut across all ages, genders and social classes. If you were poor, a goshawk could help you feed your family. If you were rich, a beautiful, big and rare bird could be a status symbol to show off your wealth, provide you with sport, and catch you another interesting dish to serve at your table – not because you couldn’t afford to buy meat but because it’s fun to say ‘Have some plover, I caught it myself!’ in the same way as it’s fun to serve food we grew ourselves.

The Book of St Albans, written by Dame Juliana Bernes, prioress of Sopwell Priory near St Albans in 1486, gives a list of suitable birds to be owned by people of different ranks. It starts with an emperor, who was supposed to have an eagle, a vulture or a merlin, works its way down through an earl (peregrine falcon), lady (merlin), young man (hobby), poor man (tercel) and prBritish Library Medieval Blogiest (sparrowhawk) and ending up, famously, with ‘a kestrel for a knave’, or servant.

Actually, the list wasn’t meant to be serious. Apart from anything else eagles aren’t particularly effective birds for falconry and nobody ever flew vultures…

There’s a letter from 1533 that says, ‘The King hawks every day with goshawks and other hawks, that is to say, lanners, sparhawks and merlins’. According to the list, none of these is suitable for a King! What it does show us, though, is that anyone might hunt with hawks and there was a wide variety of birds used. Some will have been more expensive, better hunters and cooler-looking than others.

I like to think of a bunch of Tudor noblemen comparing new falcons the way modern people compare their new gadgets like phones. They’ll have argued about which birds were best (‘Merlins? They’re rubbish! You want to get hold of a saker!’)

They’ll also have compared their bits of falconry kit: the falconer will have worn a thick leather gauntlet, sometimes richly decorated, to protect his or her wrist from the bird’s sharp claws, while the hawk will have worn a hood, a bell and strips of leather called jesses to tether it by.

In 2013 a Norfolk metal detectorist found a vervel, a tag for identifying the hawk. It was silver-gilt with the arms of Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, who was married to Henry VII’s sister – we don’t know whether the tag fell off, or whether he lost a bird that day.

Silver-gilt (silver with a thin layer of gold over it) isn’t cheap, and some birds were valuable, especially once they were trained I hope Charles Brandon’s falconer didn’t get into too much trouble!

By the way, if you see falconry portrayed in films and tv dramas, what you’re usually seeing is a Harris hawk. Harris hawks are big and impressive, so they look good for the camera, and they’re among the easiest and cheapest birds to get or train. But they’re American, and America wasn’t discovered by Europe until 1492!

Katharine Edgar is an author of historical fiction for Young Adults set in the Tudor period. You can find out more at her blog, where you can also read lots more about Tudor life, including recipes and things to try at home.

The only observation that I would make is that commoners were (I believe) prohibited from owning various types of birds, which is why so many chose to fly owls. The punishments for disobedience were pretty severe.

[Source: the falconers at “Mary Arden’s Farm” just outside Stratford-upon-Avon. This is a great place to take a young family for the afternoon – big enough for kids to explore, but small enough to not worry about them wandering too far away!]

🙂