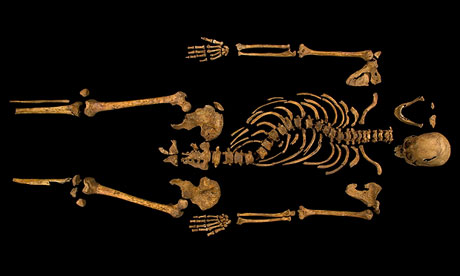

As skeleton found under a car park in Leicester has been identified as that of King Richard III, who ruled England from 1483 to 1485. Richard has been pictured as a tyrant king. There’s a story that Richard killed his own nephews, the legendary ‘princes in the tower’ in order to usurp the throne.

Nearly a century after Richard’s death, Shakespeare describes Richard as a ‘bottled spider’, a hunchback. Since Shakespeare’s time writers and artists through history have imagined Richard as a terrifying figure, whose physical disabilities are signs of his cruel inner nature.

Some historians argue that Shakespeare must have been writing propaganda to please his queen, Elizabeth I, whose grandfather Henry VII defeated Richard in battle. These historians argue that Richard’s ‘hunchback’ is an insult made up by Shakespeare, but until now, we haven’t been able to know what the truth is.

The age in which Richard ruled was certainly cruel. Two families had been fighting for the right to rule England for nearly a hundred years, and these ‘Wars of the Roses’ left neighbours and families uncertain of which side was right and which was wrong. Despite the violence of his time, there is evidence to show that Richard was a deeply religious man.

We still have the prayerbook he used all his life, which contains a long, personal prayer written for him to recite, and which he brought with him to his final battle at Bosworth field. The book was found in Richard’s tent on the battlefield, and after his death, it was kept as a trophy by the mother of the new king Henry VI. Richard’s name on the first page has been crossed out and replaced with hers: just the first of many attempts to re-write Richard’s place in history.

The discovery of Richard’s skeleton helps us to understand Richard as a human figure. Medieval fighting could be very brutal, and Richard was probably in the thick of the battle. We know that he was hit around the face several times, and two of these wounds would have been fatal. After he was killed, his body was put over a horse and carried through the town, and people would have hit at his body to show their disrespect.

A wound in the bone suggests that, when Richard’s body was carried away from the battlefield, someone stabbed his buttocks with a sword. Finally, the monks at Leicester reclaimed his body and buried him, not with the ceremony that a king might expect, but simply and in a grave that has been lost for centuries. He was thirty-two years old and had been king for only two years.

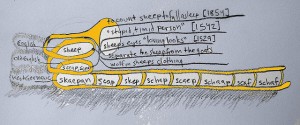

These bones hold the answer to the long disagreement beginning with Shakespeare: was Richard disabled, or was this a cruel story made up at a time when people were less accepting of disability? The answer turns out to be more complicated that we could have expected. Richard’s skeleton shows signs of a conditon called ‘scoliosis’, which means that his spine was curved to the side.

This condition is still quite common – about one in every hundred people have it –but it isn’t usually visible unless you look carefully. One of Richard’s shoulders would have been a little higher than the other. He would have been able to walk, and run, and ride a horse, like anyone else of his time. He would also have been in a lot of pain. He would have had to overcome that pain to go into battle.

To us today, Shakespeare’s assumption that a disabled man would naturally be cruel seems shocking and disturbing. We will never know what sort of person Richard was. We can only guess. But the discovery of Richard’s skeleton asks us to think again about disability.

The skeleton belongs to a man who was not seriously disabled, and whose disability would not have been obvious to people looking at him. He would have been in pain. Would these things have affected how he acted as a person, and as a king? We can’t know, but we can begin to think about what it might have been like to be living, and fighting, and dying, in 1485.

Lucy Allen is a PhD student in Medieval Studies. She works on English manuscript culture of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

Featured Image> Rex Features/University of Leicester